A push for new materials

The Leibniz-Institute for Crystal Growth (IKZ) is expanding its capacities to bring new materials to application faster—for example, in charging stations for electric vehicles

Assembly lines in the automotive industry stand still for weeks, components for household appliances are not available, and the delivery of new smartphones is delayed. The global chip crisis shows in many areas. Due to the lack of semiconductor products, countless industries were unable to deliver and were faced with plunging sales. “For experts, this crisis came as no surprise,” says Thomas Schröder. For decades, semi-conductor production was concentrated in Asia. “It is only logical that this system is very sensitive to disruptions, like the ones that came from pandemic-induced economic fluctuations.”

As the director of Leibniz-Institute for Crystal Growth (IKZ), he is well aware of how difficult it is to set up a new production line. “It requires a lot of knowledge and a lot of capital,” he says. “It takes years to create an alternative.”

However, according to Schröder, this is exactly what Europe should do. Key future technologies should be built and kept on the continent in order to be ready for future shortages. This concept has been discussed as “technological sovereignty” for quite some time now. The Federal Ministry for Education and Research (BMBF) has identified many fields of action ranging from green hydrogen to vaccines and quantum technology. Novel materials, too, are one of those fields—an ideal fit for the IKZ’s new strategy, which Schröder himself formulated when he took office in 2018. From the beginning, the researcher called upon the long-standing institute to conduct prototype development in addition to basic and applied research.

“There are three types of materials,” he explains. First, the “academic”. They are very intriguing due to their chemical make-up and structure. “Typically what happens is that the fundamentals are analysed and described, there are a few publications, and that’s it.” Protracted development could lead to unexpected problems and no private enterprise is ready to take that risk. Further down the line, there’s the second type: prototype materials. “I see these as sub-critical, we are letting innovation chances go by.” For developing technologies, private businesses require the third type: “production materials”, which are widely known and manufacturable in large quantities. “We must close this gap,” says Schröder.

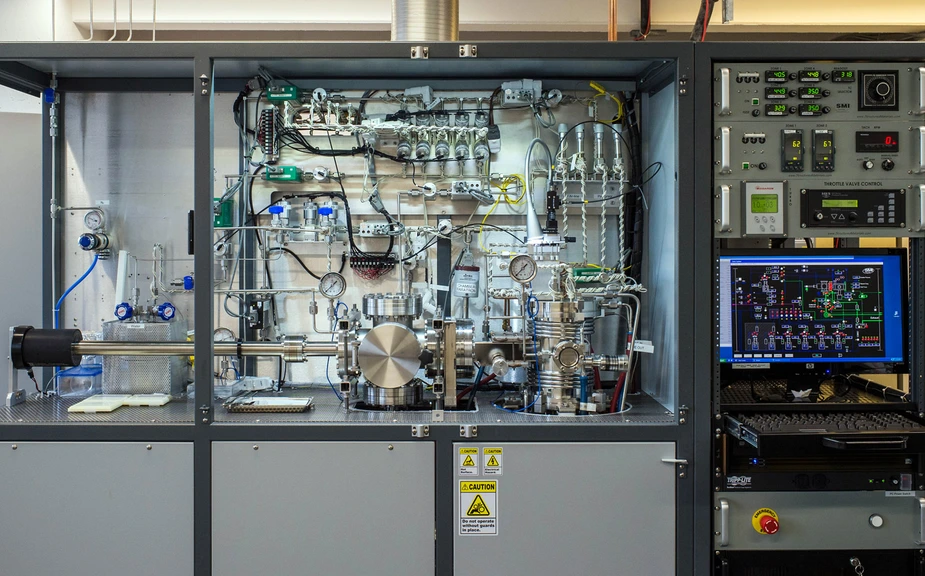

One of these materials is gallium(III) trioxide (Ga2O3). The material could be a great fit for high-performance electronics. “We need it, for example, for switches in charging stations for electric cars,” says the scientist. “The future demand for such components will increase significantly.” To find out if Ga2O3 can really do what is expected from it, it takes more than just one crystal. Fifteen or twenty of them would have to be continuously tested and optimised. “We weren’t able to produce this amount because our facilities were working to capacity on other research projects,” says Schröder.

He was now able to convince his backers—the federal and state governments. As of 2023, IKZ will received an additional 2.2 million euros every year to expand its prototype manufacturing with machines and staff. “We also benefit from all our partners in the immediate vicinity here in Adlershof,” he says. He names the Federal Institute for Materials Research and Testing, Helmholtz-Zentrum Berlin, Ferdinand-Braun-Institut, and Max Born Institute. This will be another step towards technological sovereignty but one that will have to be followed by many more. The closer things get to application, the more publicly funded research should withdraw and the industry step in. Start-ups are also important in this transitional phase and should be supported. A lack of skilled workers is becoming a growing problem. “We have to get better at attracting interested young people to the relevant courses of study and training them”, says Schröder. One idea, he says, could be to send researchers to schools to give authentic accounts of their jobs and get more graduates interested in science.

Ralf Nestler for Adlershof Journal