Blacker than coal and bound to Jupiter

Stefano Mottola investigates far-away celestial bodies. A recent mission focused on so-called trojans

When Stefano Mottola talks about his research objects, it is enormously challenging to one’s imagination. Between a few dozen and up to 100 kilometres in size and blacker than black paper or coal, asteroids circle the sun on the orbit of Jupiter. This is so far away that the little light they reflect takes more than half an hour to reach Earth.

They are called “trojans” and they are, as the planetary researcher of the German Aerospace Center (DLR) explains to us, extremely fascinating. “Trojans are small bodies ‘caught up’ in the orbits of giant planets that never got anywhere near the hot sun,” says Mottola. For that reason, its volatile constituents have not escaped, and their composition is largely unchanged from the time when the solar system was formed 4.5 billion years ago. Some call them “frozen fossils” because of that, says the researcher. “We can learn a lot about the beginning and the development of the solar system by studying them.”

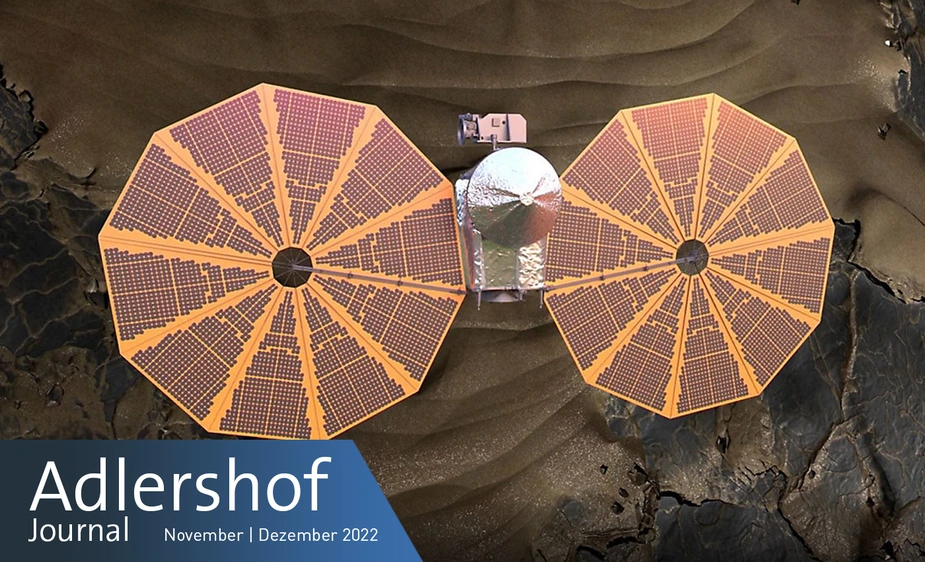

The US federal government agency for civil aeronautics, NASA, launched a probe named “Lucy” in October 2021 to visit eight such trojans. Mottola and his colleagues in the US jointly prepared the mission and helped to clarify some key points: Which destinations will it fly to? Which data will be collected? How must the flight route be planned to see as much as possible despite limited fuel?

Doing so, he was able to draw on his experience from other missions. He has been an astrophysicist at DLR since 1987. Starting out in Oberpfaffenhofen, he came to Adlershof 30 years ago, when the DLR Institute of Planetary Research was founded as the successor of the former East German Institute for Cosmological Research.

There he took part in the Japanese-German mission “Hayabusa 2” which picked up around 5 grams of sample material from the Ryugu asteroid, which is currently being examined. Mottola was also involved in the ESA European Space Agency's Rosetta mission. The hitherto most comprehensive exploration of a comet included landing on it with the research robot “Philae” in the autumn of 2014.

“That was incredibly fascinating and exciting,” recalls Mottola. Not everything went to plan, the lander bounced off the comet twice after touching down and only then came to a standstill. Luckily, it survived the bouncing and sent valuable data back to Earth. The Adlershof-based researcher cried and cheered together with his colleagues at the ESA control centre in Darmstadt.

There will be a Lucy-related meet-up soon in the US but not until April 2025. Plans for the fly-by of the asteroid “Donaldjohanson” are underway. The first trojan, which goes by the name of Eurybates, will be reached in late 2027. “In order to be able to observe as many trojans as possible, the probe will not swing into orbit but take its measurements while flying by,” says Mottola. “There is only one chance, and we have to use it.” The orbiter is already on its way to the next trojan. The Adlershof-based researchers will use the available data to determine what Eurybates’ surface looks like, whether there are hills and values, and whether the distant body is round or just an irregular pile of rubble.

There won’t be much of a waiting period until the passing of the trojans for Mottola. His days are filled with further research projects and coordination efforts for Lucy. The researchers from the participating counties get together for phone conferences almost daily to bring each other up to speed and coordinate.

The mission is planned until 2033 by which time the fly-by of “Patroclus” and “Menoetius” will have taken place. “By that time, I will be long retired,” says Mottola. I hope that I will be healthy enough to witness that phase of the mission as a guest researcher.”

Ralf Nestler for Adlershof Journal