Getting the words out

The German courses at IGAFA are not about perfect grammar – more importantly, they help to start conversations with others

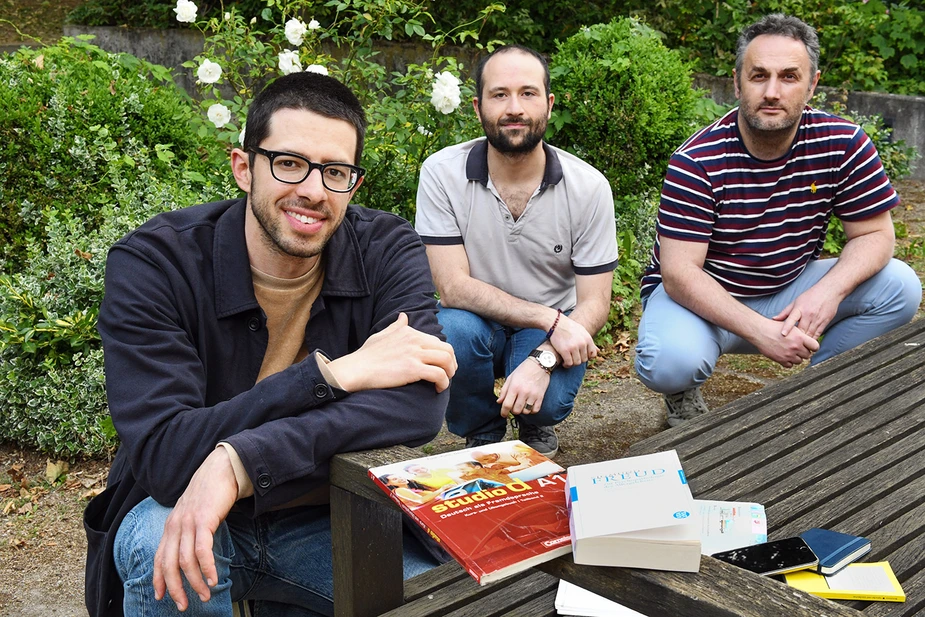

‘At the office, everything is very international and we speak a lot of English,’ says Ardian Gojani, who came to the Adlershof-based Federal Institute for Materials Research and Testing (BAM) three years ago and develops procedures for food analysis. This is not a problem for the Kosovo native. Gojani, who lived in Japan and the US, speaks fluent English. ‘But in my everyday life I need to speak German. I need to talk to the teachers of my two kids, for example.’ Additionally, the family is tired of moving and plans on staying in Germany for the time being. For these reasons, he is now learning the language.

Gojani visited a free course offered by IGAFA (Joint Initiative of Non-University Affiliated Research Institutes in Adlershof e.V.). The lessons take place in small groups, either at beginner or advanced level, once a week for 90 minutes.

‘Normally, we meet in a conference room of the IBZ guesthouse, Wilhelm-Ostwald-Strasse 3,’ says Yanik Avila, the course instructor. ‘Due to the coronavirus pandemic, we’re moving the lessons to Zoom meetings.’ Incidentally, this is also the way the research for this article was done. Owing to his carefree nature, he can easily create a feeling of closeness despite the lack of proximity. With his lively body language, Avila tells us the story of how he became a German teacher: first, he studied German, philosophy as well as literary studies and comparative literature in Zurich; then, as a fellow of the German Research Foundation (DFG) he came to Germany for his PhD and soon moved to Berlin. ‘I started giving lessons to bridge the gap to my graduation,’ he says. It was important to him not to start a job at university because he wanted to meet people from all walks of life. He then grew increasingly fond of teaching. ‘What I like most about teaching a foreign language is that it brings me together with very different people all the time,’ he says. ‘I am also genuinely fascinated by languages in every way. What’s more, this mode of teaching also gives me a way of pursuing all these different aspects of life and various interests – and to talk to other people about them.’

Avila’s goal is to enable students to express what their thinking instead of insisting on flawless declension and conjugation. ‘None of these people have time for that.’ As physicists, chemists, or biologists, most of them are very busy. ‘There is no comparison with the participants of my intensive courses that I offer at another school in Berlin’ he says. ‘Four time a week for three hours plus homework – this has proven to be a good and effective amount.’ To the clients in Adlershof, learning German is one of many projects.

‘I also tried courses online,’ says Ardian Gojani. But it was hard for him to get motivated. ‘There is always something more important,’ he says and laughs. At Yanik Avila’s courses, there is a fixed schedule and a demanding teacher, who only slips into German whenever there’s an emergency. The rest of the time everything is spoken, read, or listened to in German. This has not been changed by moving lessons to Zoom. Sharing his screen, Avila has everybody jointly solving written tasks, plays listening comprehension exercises via audio, while headsets and webcams make possible lively interaction. Gojani enjoys the intensity and the socially distanced lessons don’t bother him. It is more challenging for Avila because he finds it harder to gauge the mood of the group and sometimes a joke might get misunderstood. ‘I appreciate the measures, but I will be glad when they’re over,’ he says.

In-person instruction might return after the summer break. Anybody interested is welcome to join.

By Ralf Nestler for Adlershof Journal