Tracing the Causes of Anxiety

HU Psychologists offer assistance to patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder

They incessantly wash their hands out of fear of contagious diseases or drive down the exact same route again and again out of fear of having caused an accident – obsessive-compulsive disorders render a normal everyday life impossible. The Institute of Psychology of Berlin’s Humboldt-Universität not only treats such patients, but also examines the causes of these afflictions and work on future treatment methods.

Mental diseases are on the rise: in Germany, the cost of these illnesses in could rise to up to 32 billion euro by 2030, not counting indirect costs caused by work absence. Twenty years ago, mental diseases were a minor factor in statistics on work absence and the inability to work. The 2015 health report of the BKK, the umbrella organization of the company health insurance companies, lists them as the second most second most common cause. These alarming figures have many reasons which include the increasing stress in a meritocratic society, but also the fact that the afflicted increasingly open up, because the taboo has been lifted from mental diseases.

Such patients can turn to the Hochschulambulanz für Psychotherapie und Psychodiagnostik, the psychiatric walk-in clinic of Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin (HU) in Adlershof. Managing director of the HU’s Institute of Psychology, Norbert Kathmann, is responsible for patients with obsessive-compulsive disorders. Some of them suffer from the fear of spreading deadly diseases when they come in contact with dirt. This can lead to obsessive cleaning, but also to a horror of even leaving the house. “In some cases people are anguished by obsessive thoughts. They can be very shameful, for example, if a mother can’t help thinking she might harm her child.”

How does one help people who can’t help having crushing thoughts and imaginations? Kathmann and his colleagues resort to so-called cognitive behavioural therapy. The first step is to get to the bottom of the problem in therapeutic sessions. These are followed by exercises in which the patient confronts his fears together with his therapist and alone at home later on. “The patients learn that nothing will happen when they confront the alleged dangers and overcome their fears. One exercise is to touch dirt despite their fear of deadly bacteria,” says Kathmann. As simple as this may sound, it usually is a lengthy process. The patients have to go through 60 therapy sessions. The exercises are made to fit patients in great detail. This benefits about 50 to 80 percent of patients. Some suffer a relapse later on. Without therapy, says the psychologist, obsessive-compulsive disorders cannot be handled.

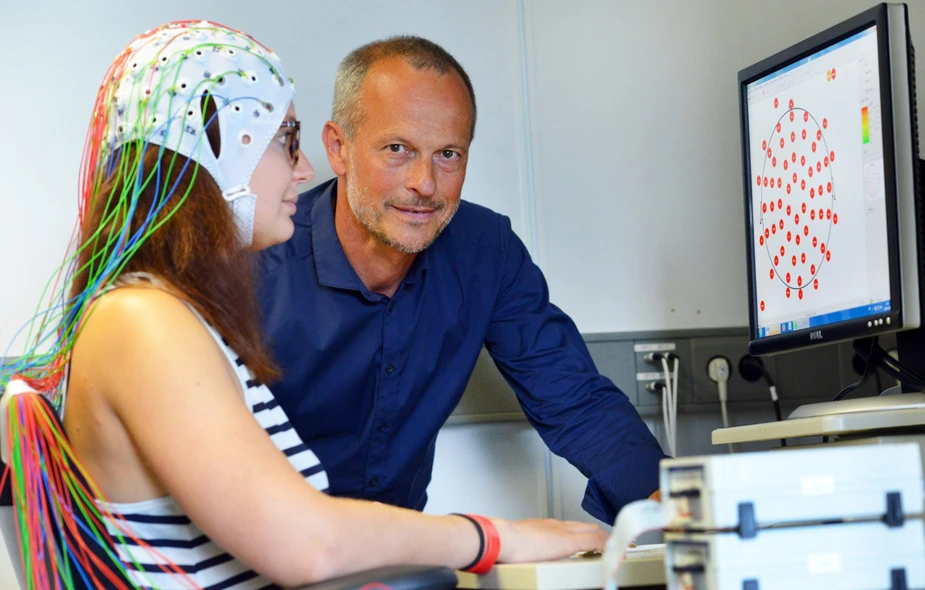

Most of Kathmann’s patients also take part in a research programme, which examines the causes of obsessive-compulsive disorders using neuropsychological experiments. The researchers look at what happens in the brains of their patients during stressful situations and compare it to mentally healthy people. The test consists of the subjects having to choose between right and wrong by pushing a button. “OCD patients produce a heightened alert signal in their brain for possible mistakes, even after successful therapy,” explains Kathmann. It remains unknown, whether these “vulnerabilities of the brain”, as Kathmann puts it, have genetic causes or are milled into patients, so to speak, by a fear-ridden family environment.

The 59-year-old wants to keep researching in that direction in order to reach a more effective treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorders. Cautious experiments with magnetic brain stimulation exist already: “We believe we can achieve better results with targeted brain stimulation than with medication.” In light of the rise of mental diseases, his discipline should also think about the uneven distribution of therapy: “In Berlin-Charlottenburg, there is a therapist on every corner, whereas you won’t find any in rural areas. I see ample room for improvement.”

By Claudia Wessling for Adlershof Journal