3D-printed lunar dust

TIWARI’s earthly and extra-terrestrial missions

The Adlershof-based 3D-printing start-up TIWARI Scientific Instruments (TSI) works for many terrestrial customers, including car, plane, and machine builders. However, founder Siddharth Tiwari’s thinking goes beyond earthly problems. As part of Galactica, an EU project, he is looking for solutions to print everyday objects and textiles on the moon. The building material: Regolith—better known as lunar dust.

He is fluent in Italian, German, English, and Hindi, studied machine building in his homeland, India, before he took the opportunity to move to the renowned aeronautical engineering institute at Politenico Miliano when he was 20-years-old. Siddharth Tiwari studied for a master’s degree there—and then started over once more in a new country with a new language, when the former DLR spin-off Active Space Technologies lured him to Adlershof. Now he is setting up his 3D-printing start-up TIWARI Scientific Instruments (TSI) and already has four employees. His team is currently starting to produce its own 3D printers.

For the start-up phase, TIWARI temporarily moved into the Darmstadt-based Business Incubator of the European Space Agency (ESA). “That was important because, in addition to seed money, we received technology support and simplified access to the elaborate certification required for our 3D-printed parts in the aviation and aerospace industry,” he explains. Moreover, launching in the ESA incubator turned out to be a seal of excellence of sorts, which has already made large car, plane, and machine-building corporations aware of what the Adlershof-based team is doing. For them, TSI takes over 3D printing orders, feasibility studies, and expert support in looking for materials. They consist of metals such as stainless steel, titanium, and copper as well as ceramics, some of which are high-strength, including silicon carbide and nitride, zirconium dioxide or aluminium oxide.

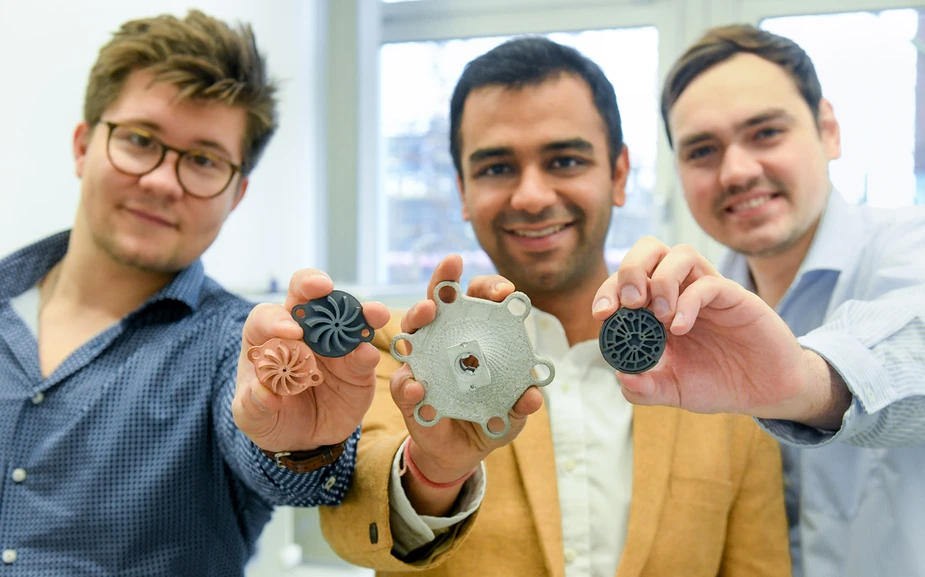

The founder has a range of printed high-precision components made from these materials, which often do not reveal what they are made of at first glance. One of them is a very robust-looking spring element made of titanium, which can absorb massive impact on landings. There’s also an inconspicuous metal plate with two inlets. “A heat exchanger, lined with fine canals,” he explains. This is made possible by using FFF, fused filament fabrication.

TSI mixes plastic filaments with whatever metal or ceramic powder necessary. Extruded through a fine head and deposited layer by layer, they ultimately become a building component. Subsequently, the plastic can be removed using a thermal process and the porous component is densified using sintering. The fact that it shrinks during this process is part of the design. “We achieve accuracy in the 100-micrometre range,” says Tiwari.

While TSI can use off-the-shelf filaments for projects in earthly industries, the current EU project, Galactica, is all about setting up a novel process chain for future lunar missions in cooperation with Hochschule Aalen and the company Spartan Space. The building material for this is stored in a mundane plastic box. Regolith—better known as lunar dust. This valuable and fine-grained material does not come from the moon. It is an earthly copy of material samples collected by the Apollo 11 crew there in 1969. TSI has printed a collection of samples with varying flexibility, which future crews will then use to manufacture everyday objects on the moon. Their goal is to create a cycle with all the ingredients from the onset. “Because it costs almost a million dollars to transport one kilogram of cargo into space, the aim is to use materials that are available locally,” the founder explains. In the distant future, he says, they could be successful in melting down aluminium-rich space debris and bringing it into form using printed regolith molds. For now, however, their mission is to establish a robust process chain for 3D printing with lunar dust.

Peter Trechow for Adlershof Journal